Heather is now a poised and confident adult with many friends and meaningful employment, but when I met her she was a tiny, frightened four year old trapped in an uncooperative body.

I first encountered Heather when I accompanied my son to his first day at a new school. Small for her age, Heather was clinging to her older sister who was trying to enter the same fourth grade classroom as my son. Her sobs wracked her small body – not the petulant whimper of a child denied what she wanted. It was a cry of terror. And it didn’t stop after the first day or week of school. Her morning meltdowns went on for weeks. Why would a child be so consistently distraught once the rhythm of the school year got started?

Eventually I got to know Heather’s mom and learned why Heather was so miserable. Heather had been diagnosed with dyspraxia.

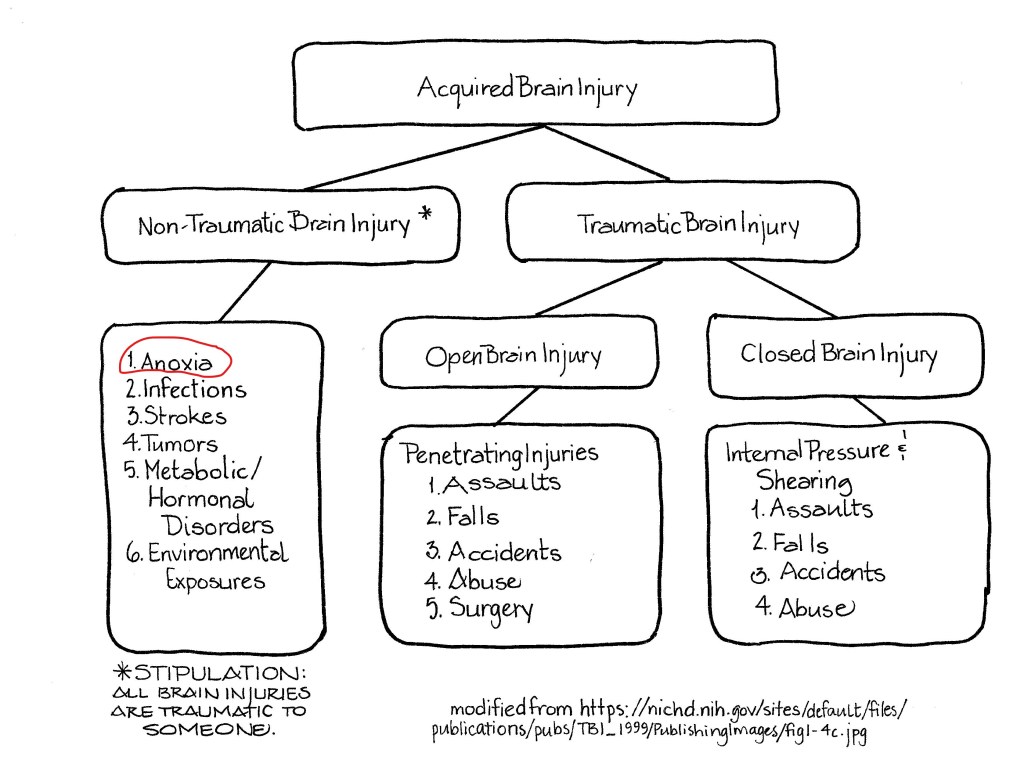

In adults, dyspraxia can come on after a brain injury or stroke and sometimes it’s a sign of dementia. Children with dyspraxia usually have motor learning difficulties, but may also have speech and/or oral dyspraxia.

Motor dyspraxia involves difficulty coordinating physical movements. Kids with this diagnosis are generally regarded as clumsy. They may have problems walking up or down stairs, hopping, or developing hand-eye coordination and tend to be messy eaters – much more so that the average sloppy kiddo. Mysteriously, to observers, children with motor dyspraxia may be able to perform a task one time, and be unable to repeat the same task later.

Children with speech dyspraxia may:

- find it difficult or impossible to make or repeat certain sounds.

- pronounce the same word differently each time they try, but not correctly

- have difficulty with intonation — they may speak in a monotone or not be able to modulate their volume

- have a limited vocabulary

- speak more slowly than other children their age, pausing often between words

- contort their lips and tongue when trying to pronounce words.

Children with oral dyspraxia may have trouble with eating and swallowing.

Heather’s tiny body moved like a marionette, but, more importantly, her speech was incomprehensible to all but three people in the world – her parents and her sister. The parents worked outside the home and her sister was in school so five days out of most weeks, Heather was in preschool with people who didn’t understand her. It was torture. She had been in some combination of speech therapy, occupational therapy, and physical therapy since she was a toddler, but her speech remained unintelligible to everyone except her family.

Heather’s birth had been traumatic. She was born blue and floppy with the umbilical cord wrapped tightly around her neck. She was revived and rushed to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) where she had stayed for a several days. Her parents were able to be with her in the NICU, but contact was limited.

Once home from the NICU she was responsive to the attention of her family, but easily irritated by light, sounds, and textures. Certain fabrics caused her to scratch. As she progressed to solid foods, certain ones were hard to swallow. As time went on, she had problems with language acquisition although it was clear she understood what people were talking about. She enjoyed parallel play with other toddlers, but once the others started refining their speech, Heather felt isolated. Now, as a preschooler, the isolation was overwhelming and the dread she felt each morning was evident.

I had just acquired a new neurofeedback system that purported to be more engaging for children, so I invited Heather and her mom to come try it out. We did site specific frequency and amplitude training, after Heather ascertained I am a good witch. (According to her four year old logic, all gray-haired women were witches.)

Because young children have extremely plastic neurology, they tend to respond quickly to neurofeedback. Within a few sessions, Heather’s speech therapist was noting that all their work over the years had suddenly “kicked in” and the physical therapist commented on how Heather was becoming more coordinated.

A whole new world opened for Heather. She was able to interact with people outside her immediate family, was able to have and attend birthday parties, go to friends for sleepovers, and enjoy being called upon in class. No more meltdowns. Her point of pride was recording the outgoing message on the family’s home answering machine, speaking clearly & distinctly.

Leave a comment